In January 2025, we set off for two weeks in Japan with the main goal of visiting producers of traditional fermented products and trying to bring some experiences back to the Czech Republic. And how did it actually turn out?

The idea was born long ago, but it took concrete shape in the fall of 2024 when we were sitting in our facility in Otročiněves with our Japanese customers from Germany, Takuji and Yuka, talking about all sorts of things. We mentioned our dream, and since Takuji and Yuka have suppliers in Japan, they offered to try to arrange a few such visits, as they were also interested themselves. And because Japanese precision, honed by ten years in Germany, is a formidable combination, a detailed trip itinerary was soon created.

And so, we went.

In this text, I’ll skip the amazing travel experiences and tourist spots, which are well described in many travelogues. I’ll also skip the incredible culinary delights, which are beyond my ability to describe, and I’ll leave that to Danča Bystrická, a chef at Bang in Brno at the time, who traveled with us.

I’ll focus on the production facilities we had the chance to visit and try to share a few experiences in the hope that you’re interested in how such traditional ferments are actually made.

That’s why we chose producers with traditional production methods. Those who don’t heat or pasteurize miso, make koji by hand, and use tools that are decades old in facilities where their family businesses, typically, have been based for centuries. That’s what inspires us and the path we’ve taken ourselves. Industrial lines can wait for another time, or maybe never 😊

1. Marukawa Miso Factory

This was the highlight. Just the welcome with a sign saying “Welcome Kojibakers” in their shop at the entrance to the building hinted that it would be warm and pleasant. And it was.

The factory is owned by one family for several generations, and they devoted almost the entire day to us. Through various stories from their history, their philosophy of why they produce organic products, tastings of miso pastes, and even a full lunch feast made from their products, we got to a detailed tour of the factory, a description of production processes, and how they’ve evolved over time.

I was amazed by the amount of manual labor, from filling to labeling and packaging products. Almost no automation, and in this regard, we, with our labeling machine and semi-automatic filler, might even be a bit ahead. On the other hand, they manage to produce three tons of miso every day with essentially just two people. In terms of efficiency, we have a lot to learn.

We were surprised by the similarities with us, where despite significant experiential and historical differences, some common operational elements were strikingly similar. I think both sides were pleasantly surprised.

And then came the tasting of our products. The owners’ son, a trained miso taster, dove into the tasting with full enthusiasm. He started with the grains of komekoji, which he tasted, examined under light, and studied to see if the rice was properly cooked and the koji properly grown. Thank goodness we had Takuji and Yuka with us, who confirmed that such high-quality komekoji had indeed been grown in Europe. We were proud of ourselves. And it continued with the tasting of miso paste. They said it’s ready to go to the Japanese market as is. But apparently, no one in Japan would buy it unless it came from a Japanese producer, because conservatism here is really strong.

And then came the tasting of unconventional miso pastes and tamari. Everyone was blown away. Caramel miso or buckwheat tamari were something they saw and tasted for the first time in their lives. We had to explain and show recipes for how such products could be used. It hadn’t occurred to them that miso could be used for anything other than miso soup.

We parted ways slowly. Bows were exchanged even from thirty meters away, and the beautiful feedback from the whole family was that with what we already have and what we saw at their place regarding production growth possibilities, it’s clear we’ll be the European miso kings 😊 It was nice to hear, even though we know Japanese politeness comes first.

Seeing and experiencing this was a dream come true. I don’t even know how to thank Takuji, Yuka, and everyone at Marukawa Miso Factory.

2. Fukumitsuya Sake Brewery

This was our first visit to a production facility in Japan ever. Fukumitsuya has been based in Kanazawa for 400 years, and as we learned, due to the unique source of century-old water (rainwater flows through various layers into the depths of the earth for over a hundred years, from where the brewery obtains it), they can’t even relocate. By the way, Kanazawa is an incredibly beautiful city and worth including in your itinerary if you visit Japan.

At this (oldest) sake brewery, one of the few that produces sake in organic quality, we spent several enriching hours. First, we learned a ton of details about sake production. About how important the water is, what kind and how polished the rice needs to be and in what ratio, how to make proper shubo, the alchemy with koji spores and yeast… I was just staring in awe.

Then we went on a tour of the brewery. That’s what I enjoy the most. Here, we not only saw a lot of things but also tasted them. Straight from the tanks, different stages of fermented moromi or sake from the pipes right after filtration (by the way, seeing such a filtration machine taking up half the room is awesome 😊), which is still unpasteurized. Fantastic flavor. I’m not a huge sake fan, but what we tasted at the brewery was an incredible hit.

Finally, there was a tasting session. That was just the cherry on top of an already fantastic cake.

3. Naraduke – Pickled Vegetable Factory in Sake Kasu

Naraduke, a local variant (in the city of Nara) of traditional vegetable pickling in sake kasu (kasuzuke), which are the lees or residue left after sake production.

Overall, sake kasu (English: sake lees) was the most pleasant surprise among the products in Japan for me. We have dozens of kilos of these lees at our facility, which we didn’t want to throw away but weren’t sure how they should taste or how to use them in gastronomy or further fermentation. I got plenty of both in Japan, whether by visiting a sake kasu restaurant or this very facility.

The good news is that our lees taste very similar, and we’re on the right track. Another great piece of news is that vegetables pickled in them taste excellent, and I don’t even know what to compare it to. The downside is that the whole production process takes 1-2 years… First, the vegetables are pickled in salt for several months, then moved to containers with sake kasu. These are swapped out according to certain rules during the fermentation process until the vegetables are properly salted and matured. After that, they last almost indefinitely.

At the end of the tour, the owner gave me a roughly ten-liter ceramic jar with their family crest for starting kasuzuke as a gift. The perfect present for an airplane when you’re watching every gram and centimeter in your luggage :-D

4. Nishiki Shoyu Factory

We were really looking forward to this one too, but the visit had one flaw – we couldn’t see the actual production. They said they were inoculating koji at the time, and the process is very sensitive… a shame.

Otherwise, the visit was great. We got a ton of information about shoyu and tamari, the rules of production, and even materials with recipes for different types of soy sauces. Incredible.

Then came the tasting of all kinds of soy sauces and our products as well. We’re actually quite proud of the comments about our soy tamari and miso. It never gets old hearing and seeing the surprise when masters with centuries of tradition taste our products with a five-year tradition 😊

And the hit, once again, was the buckwheat and chickpea tamari and, of course, the caramel miso. That worked on every Japanese person so far. Those wide eyes and appreciative laughter in the style of “this can’t be real, I’m floored” never fail 😊

What impressed us the most was the owner’s son and the person who basically runs everything there. Not only did he dedicate thorough attention to us at the factory, but he also accompanied and drove us around to nearby factories for two days and arranged visits even where “our” Takuji and Yuka didn’t have contacts. Huge gratitude and thanks.

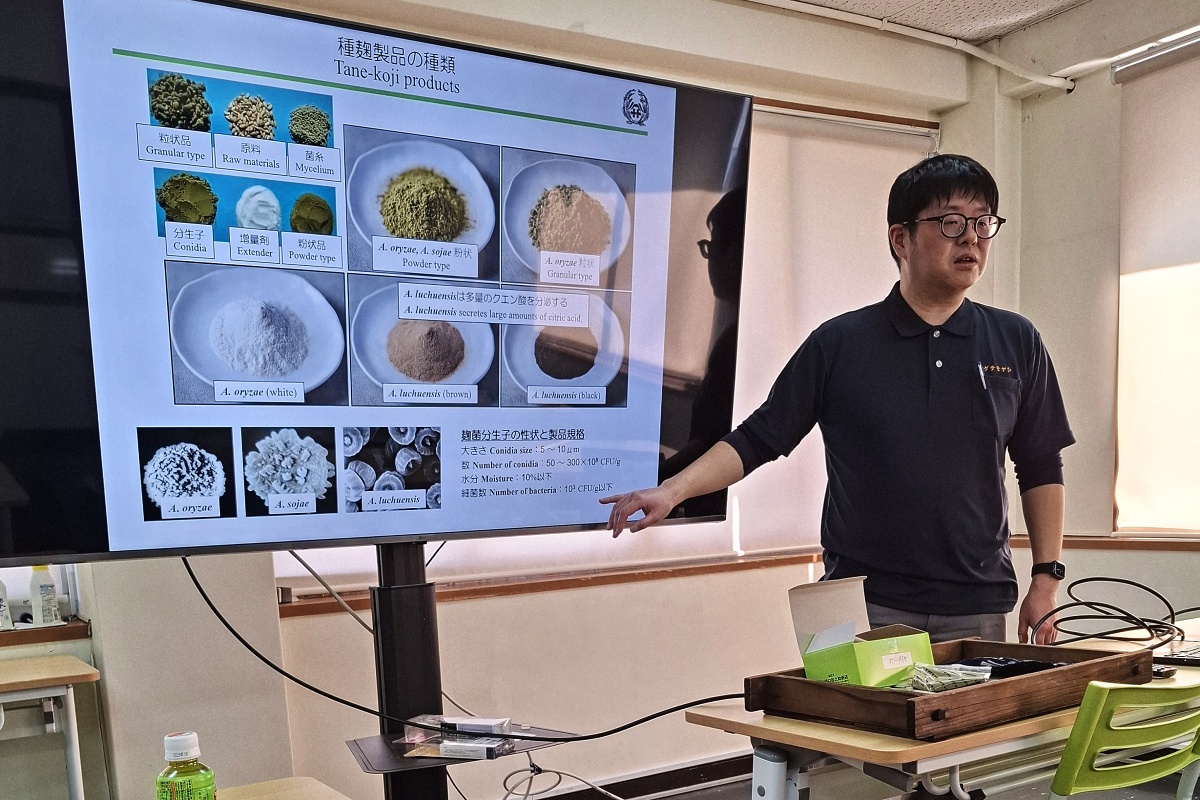

5. Higuchi Koji House

One such visit was to a koji house in Osaka, one of the few places in the world (all in Japan) that specializes in producing koji spores.

The visit began with an almost two-hour presentation with slides on the topic of koji. And it was presented by the author of several books and studies with the title “koji explorer” on his business card. Well, if I thought I knew something about koji, I sat there speechless, my hand burning from trying to write everything down. Luckily, I got the slides electronically afterward, along with contact info and an offer for consultations on choosing the right koji spores for different ingredients… I’m already intensively emailing with the Japanese koji explorer 😊

Then we visited the traditional muro – the room where koji is cultivated and where they’ve been producing spores for decades. However, they now have more sophisticated machines and lines. We saw those too, but photography was prohibited there…

6. Kitamura Sake Brewery

The second sake brewery. Interesting because this centuries-old brewery doesn’t do tours, and the only exception in recent years was for us. And that was thanks to the owner of the sake brewery I wrote about earlier.

This allowed us to see authentic “barns” and “attics” and the space for making koji, shubo, cooling rice, etc. We saw ancient wooden vessels for steaming rice, pulley systems, and other “helpers” in production. At times, it felt like an open-air museum, but with the difference that everything is functional and still serves its purpose today. I also brought sake from here for the whole Kojibakers team to taste for themselves…

7. Kyozuke – Fermented Vegetable Factory

An interesting visit was also to a fermentation facility and organic vegetable farm near Kyoto. I’m putting it last because they don’t use koji, but that doesn’t change the fact that it was great to see the enthusiasm of a group of young people for organic production and fermentation. We were both at the facility (where our hygiene inspectors would probably intervene immediately… standards are really different everywhere) and in the fields, where even in January, lettuces and local vegetable varieties grow. Many thanks.

It was an incredible experience in Japan and an unexpectedly rich offering of information, insights into production, conversations with owners, historical contexts, and tastings. It’s still hard to process, and I’m not sure if I fully realize how lucky we were here.

And that’s not to mention the tourist spots, the Japanese culture we got to experience up close thanks to our guides, or the incredibly diverse culinary experiences that I can’t even describe.

I’m very grateful for it all and am starting to gradually process the wealth of knowledge to keep improving and advancing our products. I’m really looking forward to that process.